Numerical SU(3) irreps

2021-11-27

Representation theory is a beautiful subject. The representation theory of SU(2) is fairly well known, largely because of it’s importance in physics for describing angular momentum. As is usually the case, though, spending too much time with a particular example blinds you to much of the general theory. To expand my horizons, I’m familiarizing myself with the representation theory of SU(3), which provides just enough additional complication to make things interesting. I’m also taking an incremental approach that involves some concrete numerical computations as I start to understand the concepts, which some might appreciate.

Background

Brian Hall’s notes An Elementary Introduction to Groups and Representations, arXiv:math-ph/0005032, have a nice treatment of SU(3) representations that’s approachable for a lowly quantum-information theorist such as myself. A major takeaway is that, while SU(2) only has one fundamental

representation (the defining representation of unitary matrices on with determinant 1), SU(3) has two fundamental

representations:

- The defining representation of unitary matrices on with determinant 1

- The corresponding dual representation

For SU(2), the dual representation is equivalent to the defining representation, so we miss out on this additional feature.

The Wikipedia definition of the dual representation feels strange to me with its use of transpose (usually associated with some basis dependence), so I like to think of it in a more quantum-information kind of way. If the representation maps to , then the dual representation maps to . The dagger corresponds to the inverse in the Wikipedia definition, and acting on the bra from the right corresponds to the transpose in the Wikipedia definition.

Since SU(2) has only one fundamental representation, every SU(2) irrep shows up as a subspace of some tensor power of that fundamental representation. In particular, the dimensional irrep is the totally symmetric subspace of . Since SU(3) has two fundamental representations, every SU(3) irrep shows up as a subspace of tensor powers of both representations: .

A prescription for generating the irrep associated with tensor powers of the standard irrep and tensor powers of the dual irrep is to start with a highest-weight

vector and apply lowering operators to that vector in all sequences until the vector is annihilated. Weights are determined by a maximal linearly-independent set of commuting generators for the Lie algebra.

For SU(2), the Lie algebra is the span of . No pair of these commute, so the maximal linearly-independent set of commuting generators has only one element, conventionally taken to be . For reasons

, it’s nicer to work with the complexified Lie algebra, which lets us look at without the . The eigenvalue equations for are and . The highest-weight vector for the fundamental representation is , and when we take tensor powers of the fundamental representation the highest-weight vector is a tensor power of this vector: . The lowering operator

lowers the weight, so takes . The representation for elements like and on tensor powers of the fundamental irrep is a sum of terms with the operator acting on different components of the tensor product:

For SU(3) the Lie algebra is 8-dimensional, and one can find pairs of linearly-independent elements that commute. Brian Hall picks two he calls and : Because these are like operators on two-dimensional subspaces, I’ll notate them and . We need a joint eigenvalue

to serve as the weight for these larger sets of commuting operators, so we’ll say the weight of is , the weight of is , and the weight of is , since The highest weight for the standard irrep is . The dual irrep transposes and takes the negative of the Lie-algebra elements. As with the unitaries, this corresponds to inversion (we get the inverse unitary by exponentiating the negative Lie-algebra element) and acting on the dual vectors from the right. The weights are then We then call the highest-weight vector of the dual irrep (or perhaps better, we call the highest-weight vector). The highest-weight vector for is then . The action of a Lie-algebra element on these tensor-product representations is again given by a sum of the action on each component, so, for example, This should look like a generalization of the commutator (it is the commutator for ). The highest weight in the representation is , so we’ll use that to label the irrep we get by successively applying the lowering operators to the highest-weight vector. Because we have two linearly-independent commuting operators ( and ), we have two lowering operators and that lower the eigenvalue of each of these operators. With that background, we’re ready to code up our first construction of the SU(3) irreps.

Putting it in code

I’m using my github repository where I stored the code for calculations in my recent paper Designing codes around interactions: the case of a spin (self-hosted version here) to store these new SU(3) explorations. I’m writing everything in Python, and to practice the design principle of favor composition over inheritance I’m starting with a class StandardSL3CRep to represent the standard representation for SU(3) and composing it with classes to create the dual (DualSL3CRep) and tensor-product (TensorProductSL3CRep) representations (although inheritance is apparently still too alluring for me, as these all inherit a method get_basis for getting all basis elements and the __repr__ method for displaying the object from the abstract class SL3CRep…).

With these tools in place I can now automate the process of building the subspace for the various irreps within their parent

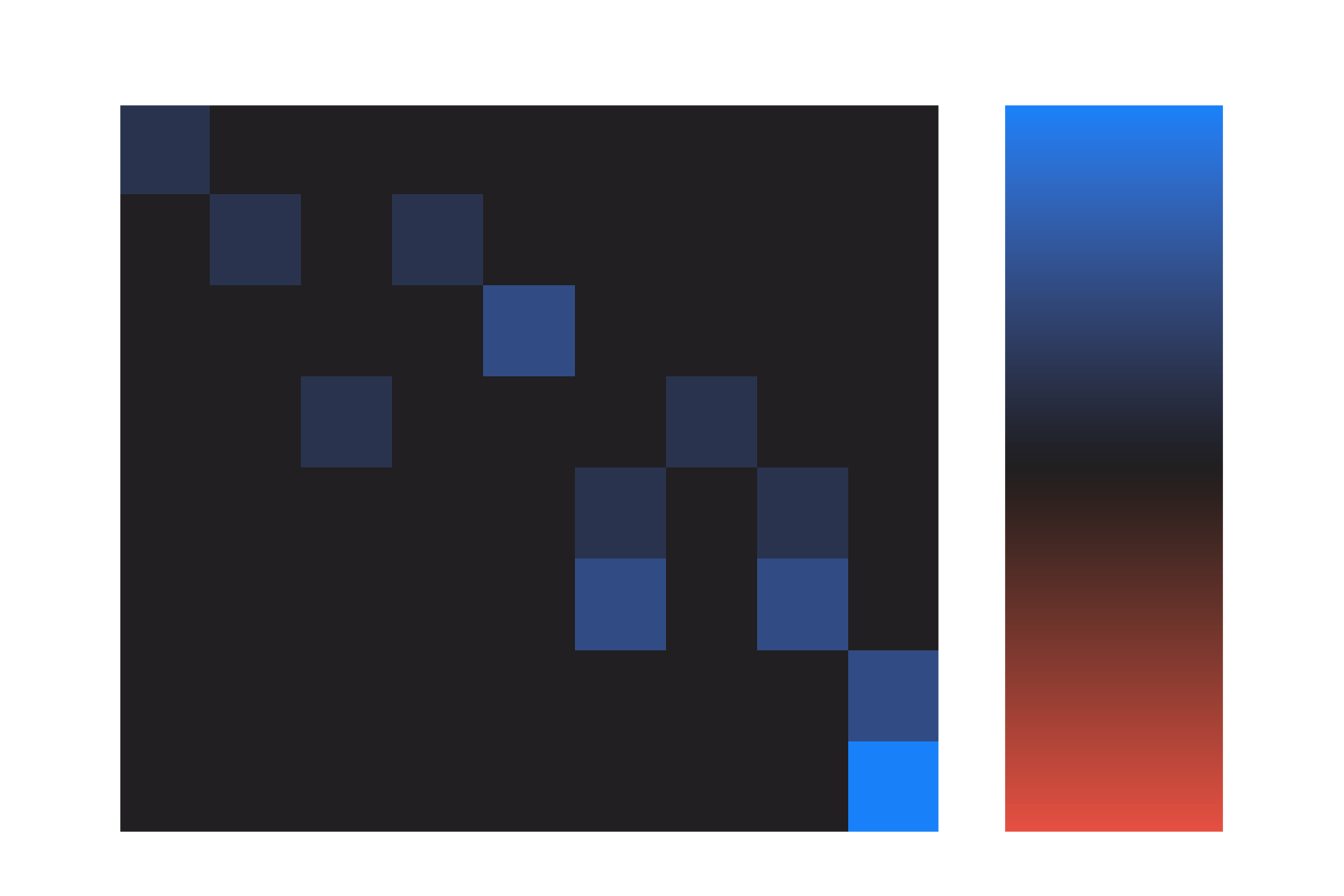

tensor-product irreps. The function get_iterative_raising_operator_applications iteratively applies what I’ve been calling lowering operators in this post to an initial vector until annihilation1 (I’m inconsistent in whether I call them raising or lowering operators, since they raise the basis index but lower the weight). When I do this for the irrep I get the original vector as well as 7 image vectors, represented as rows in the matrix visualized below:

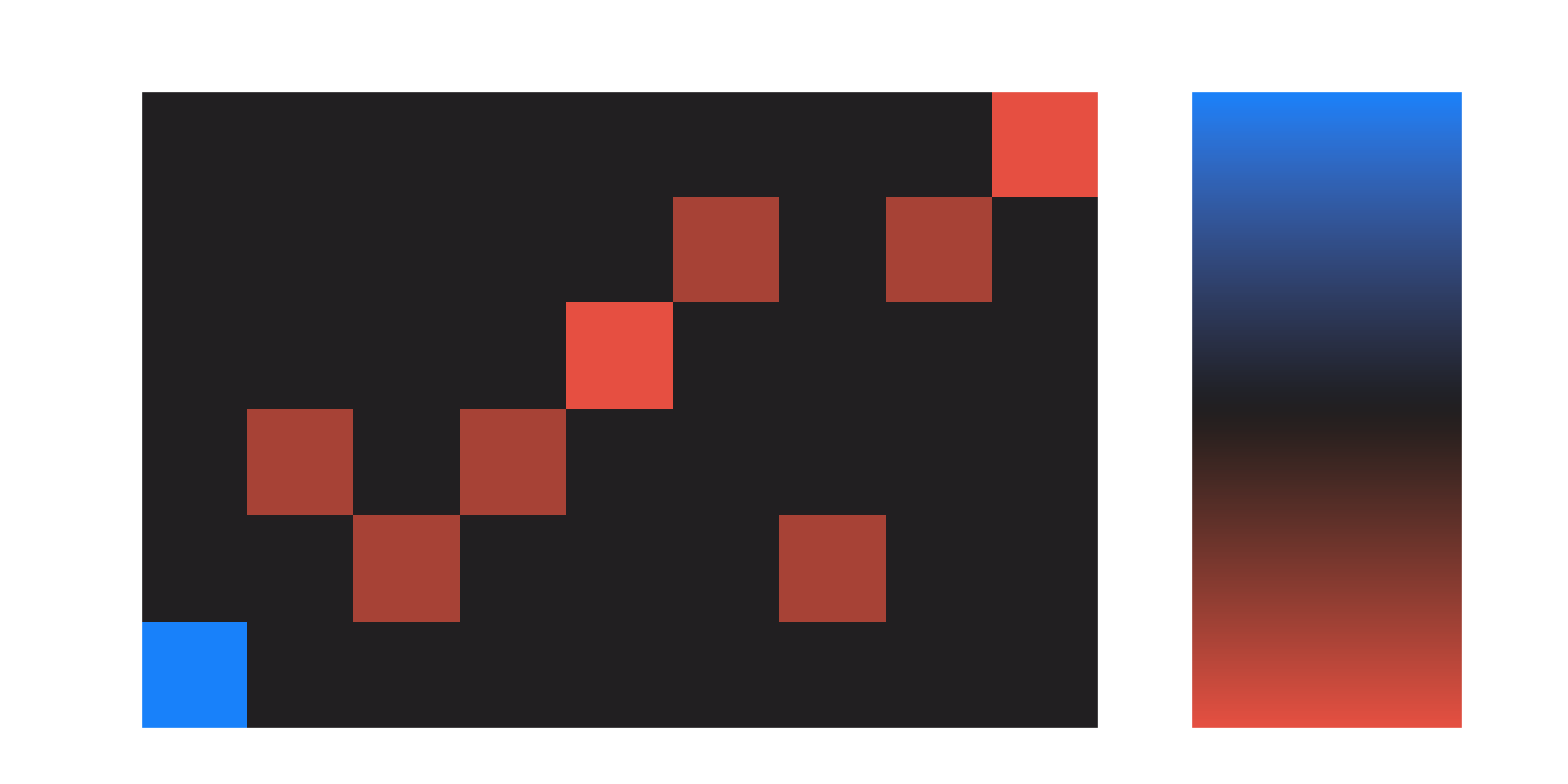

The columns 0 through 8 correspond to the tensor-product basis vectors , , , , , , , , and . Not all of these rows are linearly independent, so to get a basis for the irrep we can perform the SVD of the matrix of row vectors, keeping the right singular vectors with nonzero singular value. I have the function make_projector_out_of_image_vectors do this, although I transpose the array in that method and take the left singular vectors.2 For the irrep that gives us:

This shows us a choice of basis for the irrep, which you can fairly easily see in this case is made up of the symmetric vectors.

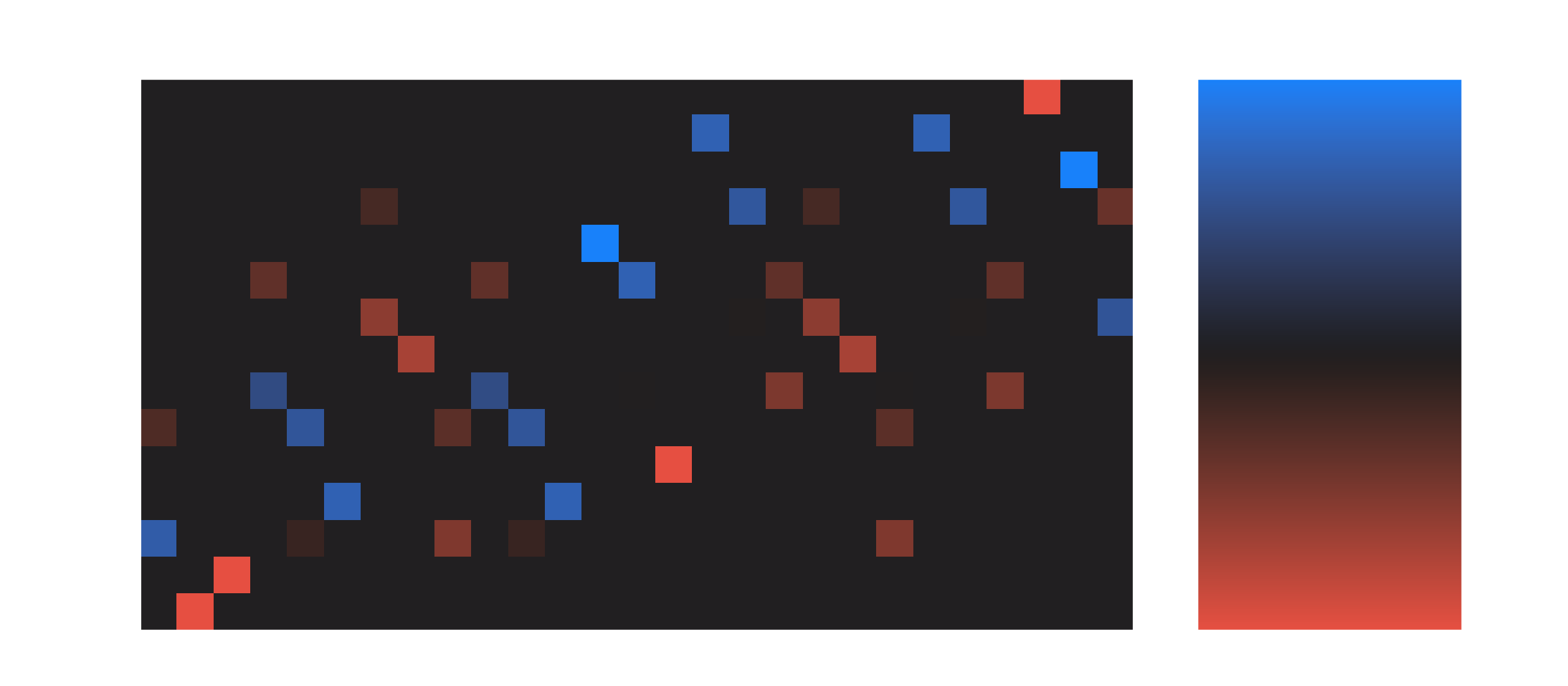

If we do this for the irrep, you get something that’s not as easy (at least for me) to interpret:

With the numerical procedure I’m using to generate the basis vectors, there’s no guarantee they’re sensible

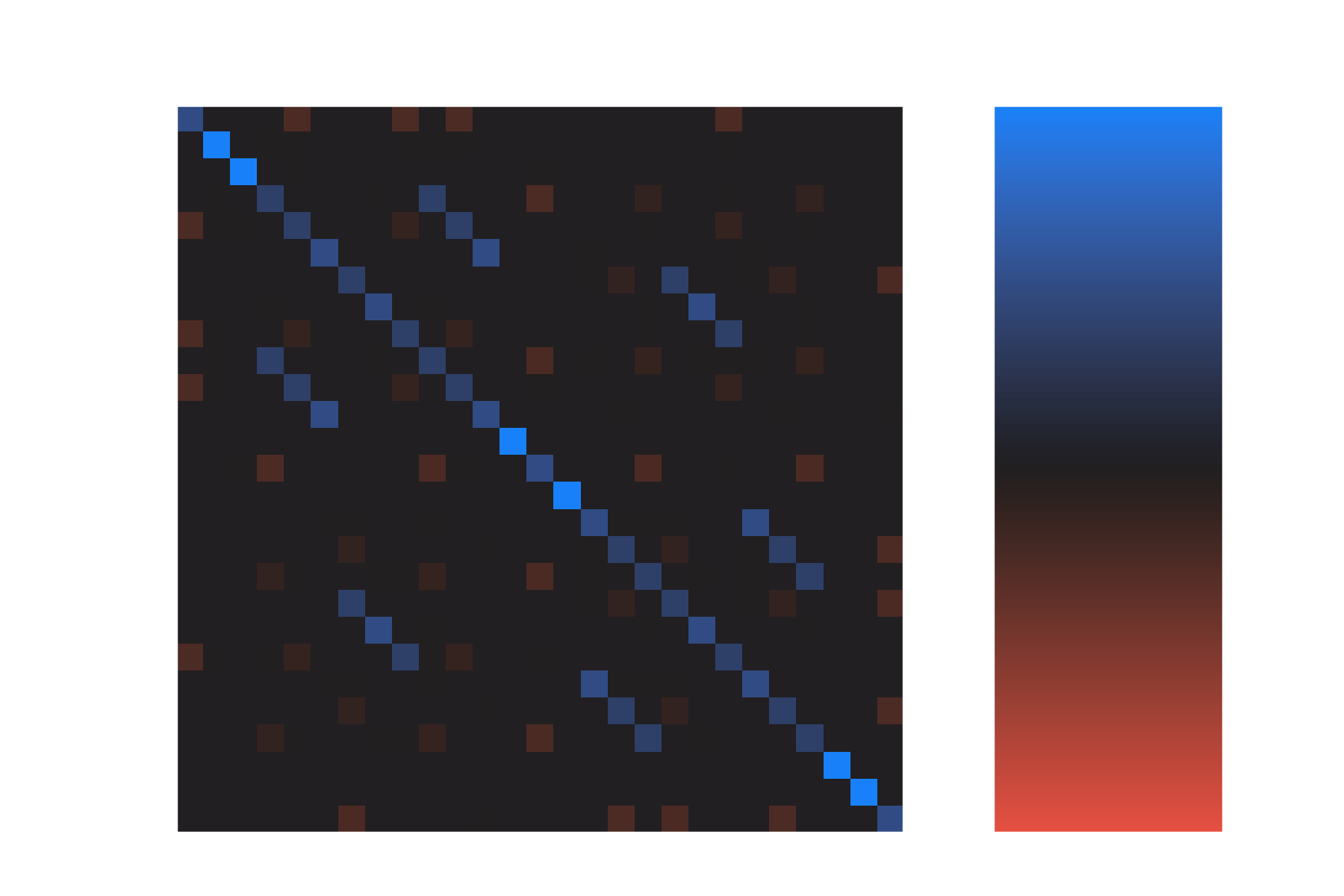

basis vectors, as opposed to some arbitrary unitary scrambling of the basis vectors. We can remove some of this arbitrariness by looking at the projector onto the irrep within the tensor-product irrep, which given the matrix of right singular vectors we construct as :

In addition to giving basis vectors that can be hard to interpret, this approach to generating the irrep basis is very inefficient. We can compute the matrix elements for arbitrary SU(3) unitaries or Lie algebra elements within an irrep, but even though the size of the irrep grows only polynomially with respect to and , our current approach requires us to build the intermediate tensor-product representation, which grows exponentially with and . This will really limit how large of irreps we can play around with using this approach. To go to larger irreps, next time we’ll look at calculating the matrix elements directly in a basis for the irrep.

Numerically one must set a threshold below which one considers the singular values to be 0.↩︎

I’m being a bit sloppy with the distinction between vectors and dual vectors , here, which I think I’m getting away with because the vectors are all real in the basis I’ve chosen to represent them. In reality, this matrix of linearly-independent rows should be thought of as a projection from the full tensor-product space to some abstract basis of the irrep, so using the right singular vectors would be most correct, since they’re dual vectors.↩︎