SU(3)-map visualization

2022-05-10

As promised, we now return to the question of visualizing linear maps on an SU(3) irrep. Let’s take as our concrete example the discrete Fourier transform. In the fundamental irrep, we can visualize it as a matrix using a complex Hinton diagram.

Here, each column is the image of one of the basis vectors under the map (the first column is the image of 0, the second column is the image of 1, and the third column is the image of 2). Since we’ve been using lines (column vectors) to depict our vectors, we end up with a rectangle to depict our linear map, since the rectangle is the Cartesian product of two lines (the input to our map being a line and the output also being a line).

If we naively tried to adapt this strategy to the triangular representation of SU(3) irrep vectors we pioneered last time, we would end up with a 4-dimensional representation (Cartesian product of two triangles, the 3-3 duoprism), which sounds pretty cool but is unfortunately not very useful for visualization in our 3-dimensional world.

We can try a variation on the matrix as a representation for a linear map, though. Instead of stacking the images of the basis elements side by side, we can stack them vertically, just like we do when representing the corresponding components in a column vector.

Each of the dark background squares indicates one of the input basis elements, just like the different columns used to. This representation is kind of like a vector of vectors

, which is sometimes how tensor products of vectors are thought of. Here we’re kind of representing the linear map as a vector in the tensor product of two copies of our irrep, which is a perfectly fine thing to do if you’re not too fussy about upper and lower indices.

For our purposes, the nicest thing about this representation is that it takes a one-dimensional depiction of a vector and gives us a one-dimensional depiction of a linear map. Leveraging the same strategy, we can take our two-dimensional depiction of a vector in an SU(3) irrep and obtain a two-dimensional depiction of a linear map on that irrep.

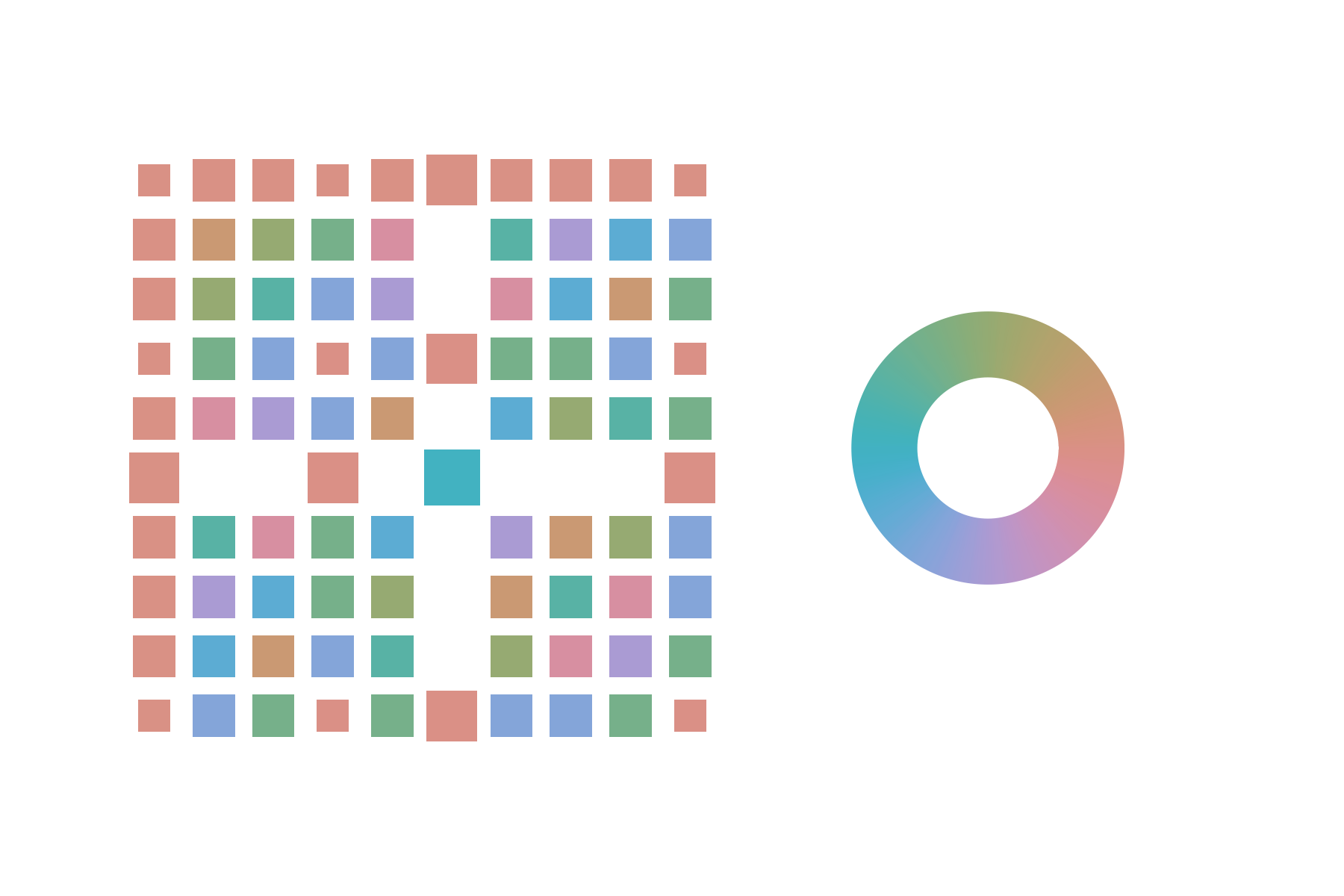

Here each of the dark background triangles indicates one of the input basis elements. This representation really starts to pay off once we go to larger irreps. Recall the representative for the Fourier transform in the irrep, when depicted as a matrix.

Better than looking at the numpy array printout, but still rather jumbled. Now rearrange the matrix entries into our new nested-triangle depiction.

Immediately the gaps in the matrix make sense! There are obviously three classes of image vectors, determined by how far away the input vector is from the center of the triangular grid of basis vectors. One can also see the phases gradually start to oscillate

more rapidly among the components as one descends through the rows of input vectors.

The code necessary for creating the complex Hinton diagrams for SU(3) vectors is uploaded to the same github repository where I’ve been putting the code I’ve developed for these blog posts. Making the linear map depictions is a matter of translating these vector depictions around and optionally putting background triangles behind them, which isn’t currently in the repo.

Since I find these diagrams so stunning, here is a parting depiction of the Fourier transform in the irrep, with the dark background triangles removed.