Parametrization independence in gradient descent

2018-12-22

This past year I had a conversation with David Meyer at the annual SQuInT meeting that got me thinking about gradient descent. Obviously it didn’t get me thinking too hard, since it’s been almost a year and I’m just now getting around to writing about it. Nevertheless, I was bothered by the parametrization dependence of gradient descent.

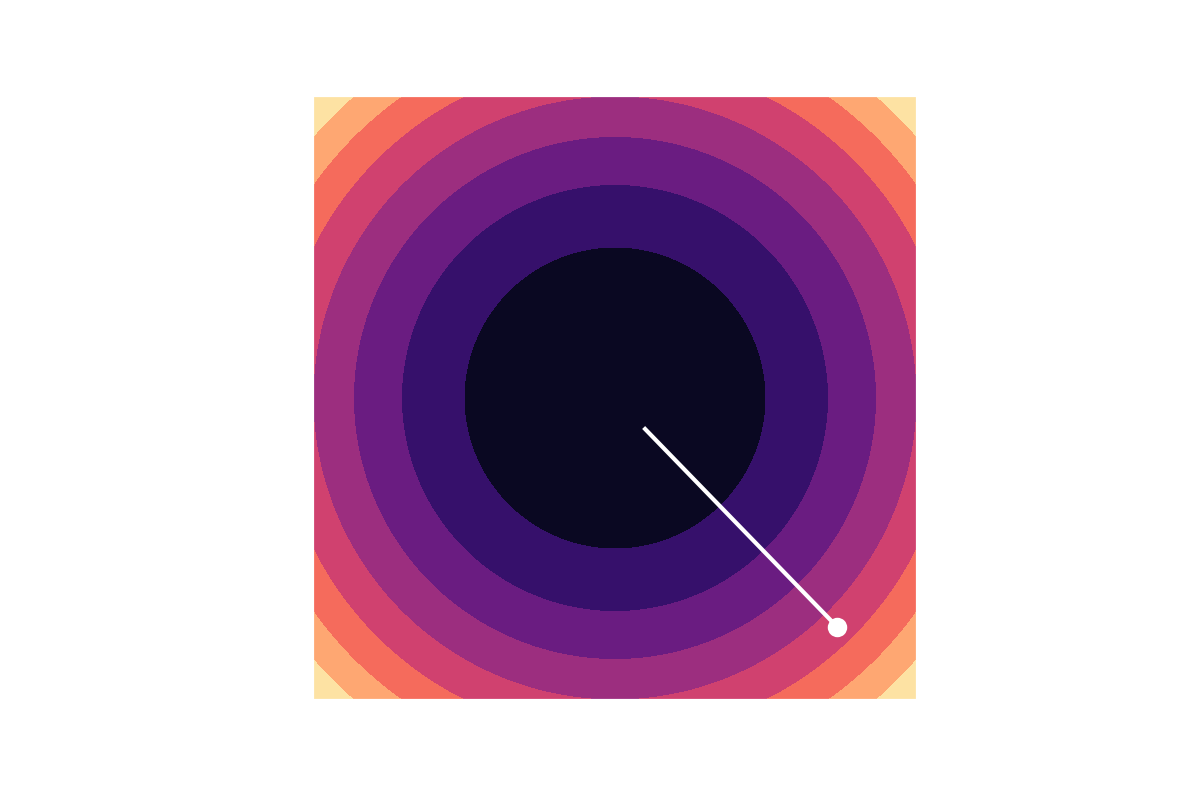

The parameter dependence that bothered me is most simply illustrated by a gradient-descent path for a simple quadratic function . When this function is represented in coördinates such that the matrix is proportional to the identity matrix, gradient descent takes a straight path toward the minimum.

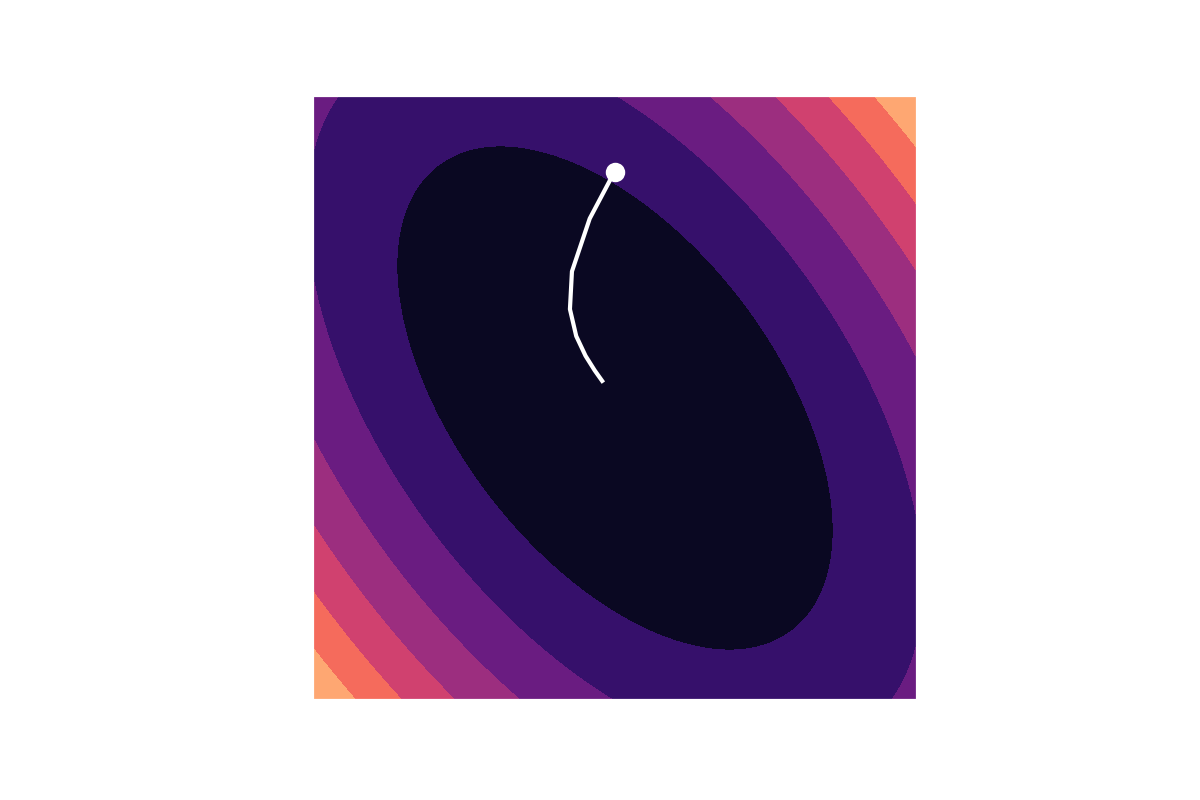

However, if you use a different set of coördinates, gradient descent takes a more meandering path.

The problem here comes from the fact that the gradient doesn’t properly tell you a direction and speed with which to move. It’s more of a tool to tell you how much the function will change if you already have a direction and speed in mind. In the language of differential geometry, the gradient—or differential—of a function is a one-form, whereas the objects that tell us how to move are vector fields. Sometimes it’s possible to sensibly convert a one-form into a vector field, but this requires deciding on a way to measure distances between different parameter points . In other words, you need a metric.

Gradient descent chooses a metric in a rather arbitrary way: it just uses a metric proportional to the identity in the coördinates you used to define the problem. This of course means the performance of the algorithm will be tied in some way to an arbitrary parametrization choice.

If you find this as distasteful as I do, you’ll be glad to hear that there are some ways to make the algorithm less arbitrary. For this, we will need the Hessian.

The Hessian of a function is a square matrix with second derivatives of the function as matrix elements: . Because the Hessian is built up from derivatives, it acts kind of like what a differential geometer would call a covariant 2-tensor. If the function is convex, this 2-tensor will be positive, and can be used like a metric. In order to convert a one-form into a vector we need a contravariant 2-tensor, which we now have in the inverse of the Hessian. Applying this logic gives us the technique of Newton’s method in optimization, which is kind of like a parametrization-independent formulation of gradient descent!

Differential-geometry purists will rightfully object that the Hessian (as I’ve defined it) is not a covariant tensor, since it’s made from partial derivatives instead of covariant derivatives, and therefore there is still an arbitrary choice of parametrization lying around. This highlights a fundamental choice of metric that still needs to be made at some level. However, if the only kind of coördinate transformations you’re worried about are global linear transformations, then the parametrization dependence of the Hessian disappears. This means that you can rest easy if there is a natural vector-space structure to your coördinate space, since none of the parameter transformations that preserve that structure will change the metric we’re constructing from the Hessian.